(part of this essay was adapted from The South Never Plays Itself, forthcoming from NewSouth Books. The book is coming out soon!)

1.

The decade is ending; pop culture still reigns supreme. Disney stands as an entertainment juggernaut, owner of 21st Century Fox, Marvel Comics, and Star Wars, and the movies from these franchise properties rake in more cash than the GDP of entire continents. We are inundated with superheroes and space opera. That’s the story of the 2010s.

Sort of. As critics deliver their best-of lists in music and television and novels and films, we look for patterns, themes, premonitions. Some critics look for takeaways. Others value the new. Some films will make almost everyone’s list: The Master, Mad Max: Fury Road, Boyhood, and Get Out. Some critics toss in a challenging movie like The Turin Horse—a great but grim movie, by the by—or some stylized, re-imagined noir like Drive. Some include well-made garbage, like Blade Runner 2049, or second-tier films from great directors; Moonrise Kingdom and The Hateful Eight, I’m looking at you. Most lists include The Wolf of Wall Street, a movie I regard with utter disdain: facile, lengthy, vile, and, worst of all, boring.

Some contrarians will elide popular/major releases altogether, as if the movies haven’t always been an uncomfortable mix of commerce and art.

The proliferation of streaming platforms has resulted in a cascade of content. Netflix and Amazon changed the game. Other companies followed. Movies that used to go straight to video now end up in your recommended list. Most are utter shit. Watching movies has become complicated, and the onslaught of choices is part of the problem.

What was this decade about, anyway?

In retrospect, the 2010s are hard to understand. We had the first black president; the continuation of two endless wars; a hardline, parliamentary Republican party roaring out of a much-needed healthcare overhaul; the proliferation of smart phones; the full transition to streaming content; the rebirth of a hostile Russia; the retreat of liberal democracies; spiraling refugee crises and a dozen, splendid little wars; and the election of greed incarnate in the United States. The promise of the 1990s—the multicultural, Internet-will-free-you-end-of-history—and the optimism of the Obama years gave way to full and total retrenchment. It is a delirious, glorious, punishing time to be alive. (As of this writing, the president has just kicked three million new people off of food stamps. Merry Christmas, eh?)

The bastards took over. And, if you were paying attention, the movies took notice.

Everyone seemed to be asking the same questions: Where are we going? What do we care about? Where does fiction end and reality begin?

Taking in an entire decade’s worth of films—eight thousand or so—is an absurd task. The Irishman should be on my list, as I can’t stop thinking about it. I haven’t yet seen The Parasite, helmed by my favorite living director, or Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. And I haven’t finished Marriage Story, but halfway through, it is flawless.

My best-of list appears in part 3—and I’ll understand if you skip ahead—but first I’m going to make the case for the movie that captures the zeitgeist of the decade most completely, not the best movie but the best film that shows what the decade felt like as we were living it: 99 Homes.

2. Released in 2014, 99 Homes uses fiction to examine the fallout of the 2008 housing crisis, focusing on a working-class family run into the ground. It is a relentless, blood-chilling saga of the dark torrents of capitalism. Realistic, vicious, and heart-breaking, 99 Homes is set in a Florida of tourist-packed hotels and palm trees, corporate raiders vaping against a backdrop of beautiful, sun-drenched misery, and invisible working people, on the margins being gobbled up by invisible machines. The movie uses the same technique as The Messenger, taking a somber and sad situation but treating it as a thriller. And just like with The Messenger, it works.

The film opens with a dead-eyed Michael Shannon, playing a hardcase real estate/banking foreclosure handler named Carver, standing in the living room of a dead man’s house. The dead man has just committed suicide; he offed himself because Carver has just repossessed his house. The next scene has a construction worker named Nash (played by Andrew Garfield) who has not only not been paid for the last two weeks of construction work he’s been doing, he’s also been informed by a bored judge that his house, the one he grew up in, the house where his mother operates her hair-cutting business, is no longer his.

When Nash tries to plead with the judge he receives this stony response: “I have 40,000 cases just like this one.” And then the gavel.

He has his young son in tow, and the two of them both believe that they can appeal the decision, and that they have thirty days to do so. They are wrong.

What follows is one of the most harrowing scenes I’ve seen, a white-knuckle fifteen minutes where the police, acting as enforcers for the banking industry, force Nash and his mother (played by Laura Dern) out of their house on Carver’s orders, and then some local dudes remove all the furniture and belongings, leaving them on the front lawn, exposed to theft and the elements.

“You’re trespassing,” the cop tells Nash. Nash carts his family to a motel, where they join the swelling ranks of the other recently dispossessed.

Being poor sure costs a lot. No work, no prospects, no home, few possessions, and son to take care of: the walls around Nash get higher and higher and keep closing in. Is America a place where you can lose your home due to banking errors? Can an individual with connections to the banking establishment swoop in and steal your home? Yes.

To survive, Nash’s first job is literally to shovel other people’s shit. It’s a post-ironic display of 21st century suffering. He seeks out the only growth industry he knows, foreclosure, and ends up working for the very man who evicted him: Carver. He begins by doing work on a beautiful water-front house with rot setting in, but quickly proves himself in Carver’s eyes.

How’s the saying go? The third world is just around the corner. Here is a diminishing America epitomized in a Florida where dreams go to die.

Michael Shannon is the star of the movie, giving his rictus features over to a malicious, yet believable performance. He plays Carver as a world-weary, jaded hero of his own mind, an uber-mensch beyond good and evil. He’s seen it all, and refuses to acknowledge his role in the fuckedupedness of the whole shebang. He is obsessed with the bottom line, and full of loathing for the petulant, whining humans who crawl and beg all around him. He rebuilds Nash into a morally compromised person very quickly; in just a few weeks, Nash is armed, stealing from foreclosed homes, and evicting people in the same style he himself was evicted. Nash gets his home back—maybe—but at the expense of his soul, his decency, his moral sense. “Don’t get emotional about real estate,” Carver warns Nash, but what he’s really saying is, Don’t care about other people. There’s no money in it.

Carver is deformed, too, by the moral rot of the world around him. In a terrifying speech, an update of Gordon Gecko’s “Greed is good,” Carver lays out the whole stinking rotten mess: “Ask the banks why they gave them an adjustable rate mortgage. Ask the government why they lifted all regulations and turned a blind eye. You, the Tanners, the banks, Washington and every other homeowner and investor from here to China turned my life into convictions. . . . Do you think America 2010 gives one damn about Carver or Nash? America doesn’t bail out the losers. America was built by bailing out the winners. By rigging a nation of the winners, by the winners, for the winners.” Gordon Gecko lays out a vision of America as a vast panoply of interlocking businesses that is, in essence, a zero-sum game. There are winners and losers. Carver delivers a much more terrifying vision, an America that has losers and survivors, no real winners at all. Welcome to the 2010s.

Nash is propelled to the edges of the real estate, mortgage rates, and human decency. Nash and the people he devours all try to follow the rules and do the right thing. They hire lawyers. They file papers. They appeal to the decency of the courts. But they all lose their homes anyway. The threshing machine doesn’t just devour the guilty or the lazy or the unlucky; it gobbles up everyone.

99 Homes takes great care to how easy it is to slide into wrong-doing, to lie and cheat and steal and put your boot on the other person’s neck, believing that it isn’t actually impacting anyone. Everyone in the movie is caught in this giant machinery, whipping back and forth from helpless to predatory. We’re come so far from the optimism of the 1940s, or the 1990s for that matter, as to stretch our core beliefs that used to be the very definition of American. In many ways, the movie focuses on the burrowing maggots squirming beneath the perfect lawns in Blue Velvet. It’s grim and hard and impeccably made. And if the movie reduces itself into a tidy and too-easy single moral choice, it’s a Hollywood film attempting to dramatize a complex national tragedy.

Do people do the right thing? Can they? Is there any escape from the labyrinth of money and deceit? A superb examination of how good people are failed, 99 Homes offers no easy answers.

Near the movie’s end, Carver awakens a hungover Nash with a single line: “Good morning, Donald Trump. We got an eviction.”

An unscrupulous real estate agent, small pistol strapped to his ankle, vaping beneath a technicolor sky. This is Florida, America, civilization—vulnerable to the prowling jackals dressed up in non-descript clothing.

I hear you wondering, is 99 Homes entertaining? Yep. The pacing is superb; the movie rips along with set pieces, confrontations, and a ratcheting tension.

Other movies circled the same issues. The Big Short details the insiders who saw the coming crisis. The Queen of Versailles paints a portrait of how even the wealthy got walloped. Throw in Vice—where the shaggy, current manifestation of the deregulating beast kickstarted the crisis in backrooms and unofficial meetings—and Margin Call, and you’ve excavated the recent history that feels like it all happened 2000 years ago, and could happen again tomorrow.

Shannon’s Carver is the ultimate villain for where we are right now. He just doesn’t care. And he isn’t alone. Jeremy irons, in Margin Call, outlines how the boom-bust cycle works exactly as it’s supposed to in a chilling speech near the end of that icy film: “What, you think we may have helped put some people out of business today? That it’s all been just for naught? Well, you’ve been doing that every day for almost forty years.”

No one is innocent. How’s that for a coda for the end of the decade? We’re all part of a system that, despite whatever good things we think it does, tears people from their homes, shoots citizens in their cars, bombs the shit out of the middle east, routinely destabilizes central American countries, and, now, separates children from their parents, putting both pens and cages.

Our country is falling apart. We have a raging deficit, a minority party in power and the racist, nativist banshees we had trapped in our collective sub-basement howling through the body politic. We are in peril, and there are no superheroes to save us.

3.

On that happy note, here’s my best-of list, in no particular order:

Once upon a Time in Anatolia—Funny, scary, beautiful, meditative, even sexy, this Turkish masterpiece follows a group of government officials driving around the countryside, looking for evidence in a murder. They find evidence, eat meals, argue over nonsense. They drive and drive. It becomes clear that some of the men are suspects, that no one is being perfectly honest, and they are looking for a dead body. Some movies seem to contain entire universes; this is one of them. As haunting a movie as you’ll ever see. The director followed up with the very fine Winter Sleep.

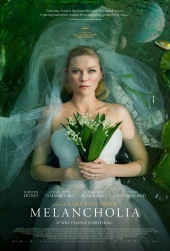

Melancholia—Lars von Trier’s stunning end of the world tale begins with a wedding and ends with the destruction of everything. Maybe. Great art has to maintain mystery, and this movie does it with spades. Two sisters reckon with a rogue planet heading towards earth’s orbit. One embraces the end with sinister humor. The other resists. What sounds grim is often funny and thrilling. Unforgettable.

The Master—Another movie that contains multitudes, a film the befuddled audiences initially and, just like There Will Be Blood has grown in stature. A rich and complex tale of hubris, madness, trauma, religious mania and the formation of a cult. A lonely, isolated veteran attempts to make his way through the world after returning from World War II. He can’t. He ends up in the hands of a L. Ron Hubbard figure, who uses and is used by the wastrel. Multiple viewings pay off; Amy Adams steals the movie, but on first viewing she barely registers.

The Social Network—The beginning of the end, eh? David Fincher and Aaron Sorokin join forces to deliver the docudrama about Jeff Zucker and the foundation of Facebook. In Fincher’s always capable hands, the business decisions of a fledgling web platform takes on the air of an epic, world-shattering horror-tragedy which, in retrospect, is exactly what it was. Filmed with technique and brio.

Springbreakers—Harmony Korine’s fascinating movie is both a wild crime jaunt and probing meditation. Four college coeds head to Florida for spring break. To pay for it, they arm themselves and rob a bank. Korine ruminates on hedonism, violence, American pop culture, and the way our country eats the youth. Unpredictable, with bizarre tonal twists and turns and a superb performance from James Franco, Springbreakers—which is also absolutely gorgeous—feels like the exclamation point to the end of the American empire.

Hereditary—Toni Collette’s finest hour, and the most unsettling horror movie I’ve seen in 15 years, perhaps longer. Trauma has taken hold in a beleaguered family, and the psychotic atmospherics heighten the overwhelming feeling of dread. Usually in horror movies, the family offers safe haven from the world’s monsters; here the family is the danger. The director, Ari Aster, followed up with Midsommar, itself a pretty damn good horror movie. It Follows was my horror movie runner-up.

Force Majeure—An austere, European art movie offering profound insights into masculinity and attraction. Also, it’s funny. A family goes on a ski trip. In a moment of weakness, the husband, Tomas, abandons his family out of fear of an avalanche. (He also, hilariously, grabs his phone first.) It turns out to be a false alarm, but Ebba, his wife, feels betrayed and bewildered by her husband’s irrational fears, as well as his inability to confess his weakness. He cannot admit to any cowardice. She begins to despise him. What follows is sort of a comedy, sort of a drama, kind of a horror movie, kind of a sociological treatise, and absolutely unforgettable.

The Square—Director Ruben Ostland’s follow-up to Force Majeure, The Square tells the story of a museum curator who, through the course of the movie, loses his cell phone, has an affair, and runs afoul of an unscrupulous performance artist. Exquisitely filmed, with superb scenes, what could have been a one-note takedown of the pretentious art world is something much more complex, how mystery and enigma can enter a life. Uncompromising and dark, the film feels like something Michel Haneke might have produced, if he had a sense of humor.

Frances Ha—The definitive statement about growing up and getting older. Frances is in her late twenties, still living like a college student, trying to fulfill her dreams of being a professional dancer, and hoping to keep her friendships in amber. Filmed in stunning black and white, the story of Frances’s disillusionment and reconstitution is a wonder. Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach deliver the best movie of both of their storied careers.

Get Out—Lightning in a bottle. Director Jordan Peele, famous for his sketch comedy show Key & Peele, presents a fabulous horror movie about white desires and black bodies. An urgent, and still relevant social message is rattling around in here, not that it matters. The movie is a funhouse thriller that works under your skin but is fun to watch. Perhaps the movie that best presaged our current miasma of systemic racism, white privilege, and the suburbs.

Winter’s Bone—The little movie that could. Adapted from a very fine Daniel Woodrell novel, Winter’s Bone follows Ree Dolly, a teenager living in the Ozarks, as she is confronted with a stark choice: prove her missing father is dead, locate him, or lose the family property due to bond. Ree enlists the help of her terrifying uncle, Teardrop, and what follows is an astonishing family crime drama, filmed on location in the backroads and trailer parks of Arkansas. A tour of rural hell.

The Act of Killing—The 20th century in miniature. Backed by documentary icons Werner Herzog and Errol Morris, this unsettling documentary follows two men responsible for ghastly atrocities after a coup in 1960s Indonesia. Their names are Anwar and Adi, and the movie consists of flamboyant re-enactments of their brutality. The director, Oppenheimer, pushes them to participate first as themselves and then, later, as the victims. Anwar in particular moves from jocular apathy towards his crimes to an existential despair; the act of playing his former victims tears the fragile psychic protections he had erected. The mass murderer transforms, in front of our eyes, into a human being.

Birdman—A love it or hate it movie. I love it. Raymond Carver meets magical realism meets the bizarre acting career of Michael Keaton. Riggan, an aging actor, bets everything on a stage show that he is producing, directing and starring in. Things are not going well. A difficult co-star, his angry, formerly drug-addicted daughter, and a menacing alter-ego that no one else can see, Riggan is headed for an epic failure. Filmed in what appears to be a single take, Birdman is the brainchild of Mexican superstar Alejandro Innaritu, part of the wave of Mexican directors (including Alfonso Cuaron and Guillermo Del Toro). A dynamite comedy that is cynical and wild, held together by excellent performances. Innaritu followed this up with another superb film, The Revenant.

The Grand Budapest Hotel—Wes Anderson’s finest movie since Rushmore, which is high praise. A hotel story replete with affairs, hijinks, hidden rooms, art thieves, henchman, dandies and killers, this 2014 movie manages to be fun, light, and airy while also delivering a somber, meditative rumination on the vanished world of pre-war eastern Europe. Ralph Fiennes gives the performance of his lifetime as a dapper concierge juggling schemes and affairs and the innerworkings of a grand hotel. The plot? Too byzantine and ridiculous to recount here. A dazzling confection.

Hell or High Water—A caper-western hybrid that honors the roots of both genres with superb visuals and great scenes. Two brothers, one facing financial catastrophe, the other recently released from prison, embark on a bank-robbing spree, attempting to save their family farm and stave off disaster. Meanwhile, a Texas ranger (played by Jeff Bridges), seeks to outsmart the two thieves. What follows is a series of feints, ambushes, and robberies. Weirdly, it reminds me of Lonely Are the Brave. To people who say they don’t make ’em like they used to, I point to this movie right here.

Midnight in Paris—Woody Allen’s best movie since Crimes and Misdemeanors. Owen Wilson plays Gil, a struggling writer on vacation in Paris with his fiancée, Inez (played by Rachel McAdams). Gil is nostalgic for the world he never knew, and one night is transported back to the 1920s. He rubs shoulders with the luminaries of the Lost Generation, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Stein, Porter, Dali and more. He is drawn more and more into the past, while in the present-day his fiancée is entranced by a blowhard academic (played to the hilt by Michael Sheen). A fabulous little movie about the weight of history and the downside of living in the past.

Inside Llewellyn Davis—A misinterpreted little gem. Traumatized by the suicide of his former singing partner, folk singer Llewellyn Davis loses a cat, records a dumb song, gets beaten up, and travels to Chicago, among other things. The tone is downbeat, yet the movie crackles with a superb cast, great music, and a title character who is self-sabotaging. Every decision he makes is somehow the wrong one. Audiences mistook Davis’s trauma for misanthropy. The Coen Brothers best movie since No Country for Old Men.

A Most Violent Year—The gangster film is alive and well. It’s 1981 in New York City, and Abel Morales runs a trucking company. He’s ambitious and talented, but he has a problem: someone is hijacking his trucks. Each theft sets him back thousands of dollars, and his wife, Anna, wants to strike back and use her family’s mob connections. Abel is being investigated by a district attorney with political ambitions, and Abel’s company rests in the balance. Oscar Isaacs and Jessica Chastain were two of the dominant actors of the 2010s, and here they crackle as the married couple living on the edge of the law.

Moonlight—Steeped in the history of cinema, possessing a singular vision for his movies, and armed with not just top-shelf skills but also impeccable taste, director Barry Jenkins seemed to appear out of nowhere with this 2016 tale of a closeted gay black man living in poverty and on the edge of crime. Told in three distinct sections—young child, teenager and mid-twenties adult—this beautiful movie covers an astonishing amount of territory, while also telling a touching, intimate love story. And, yet, the movie is so rich, that this description doesn’t really cover it.

Computer Chess—A bizarre, and very funny, lo-fi experiment. A group of early eighties computer nerds converge on a convention hall to pit their primitive artificial intelligences against each other. A comic, and quite gentle, chaos ensues. Filmed with cheap, early eighties equipment, and handled as though the proceeds are a local access TV special, the movie has a lot to say, about where the Internet really came from, what computers are actually good for, and how unsocialized polymaths shaped our culture from the fringes. An antidote to the three-hour special effects extravaganzas.

You Were Never Really Here—My nod to the never-ending noir, crime and underworld films, always a proving ground for new directors. Joaquin Phoenix plays a traumatized mercenary named Joe. Joe’s weapon of choice is a hammer. Joe takes care of his elderly mother while grappling with the myriad demons of his past, and the suicidal thoughts that plague his present. Like any good noir, Joe is double-crossed on a job, and sets out to get revenge. An excellent movie with top-notch directing, a great musical score and yet another unforgettable performance from Phoenix, who killed all decade.

Rust and Bone—One of my favorite movies, by one of my favorite directors (Jaques Audiard), and when I describe it to people—a bare knuckle fighter and a woman mauled by a killer whale fall in love—I always hear the same thing, that the movie sounds preposterous. It isn’t. It’s exquisite. An unsentimental love story that is brutal, sexy, unabashedly romantic and thrilling. Audiard went on to make Dheepan and The Sisters Brothers, both vastly different from Rust, both of them excellent.

The Trip—Two actors playing versions of themselves travel around England’s poshest restaurants. They sit and eat. They talk. That’s the movie. But Steve Coogan and Rob Bryden, superb mimics with razor-sharp comic timing, invest the movie with wit, charm, dash, and the result is a rich and complex character study. Michael Winterbottom directs, and intercuts the two riffing and bickering with shots of the preparation of the food. There isn’t a clear metaphor and there doesn’t need to be. The Trip to Italy follows, and Coogan shifts his ruined roué into a man trying to be a good father, while Bryden begins fucking up his life. The third film is The Trip to Spain, probably the funniest of the three. The movies are a piece with Tristan Shandy, and taken together you have a sense of both men, their egos, their support structures, and their shortcomings. Each film has Coogan and Bryden dueling with impersonations, including Michael Caine, Mick Jagger, and Roger Moore. Hysterical, yet melancholy, too. They are filming a fourth movie, as of this writing.

Too Many Cooks/”This is America”—Alongside La Jetee, the finest short movies ever made. Too Many Cooks is ostensibly the credits to a 1980s sitcom, only the music never ends. The cliched ’80s shows all appear, including cop dramas, science fiction, soap operas and sitcoms. The grating repetition seems to be the point, but a predatory presence invades, warping all the proceeds into a cannibalizing blood feast. When you think you’ve figured it out, it twists into something new, offering a sinister view of American pop culture as a weapon. “This is America” begins as a music video for pop culture wunderkind Childish Gambino. But it is so rich in metaphor and visual ideas, so complex in its layers of irony and symbolism and meaning, I watched it over and over. It deals with the place of black people and black culture in America, and how violence is rewarded. The things that seem important aren’t. And, the result of centuries of violent oppression is a generation of black children indifferent to their own suffering and the suffering of others. The two films together paint a terrifying picture of America and its future. If you aren’t nervous, you weren’t paying attention.